~ Cecil Thounaojam

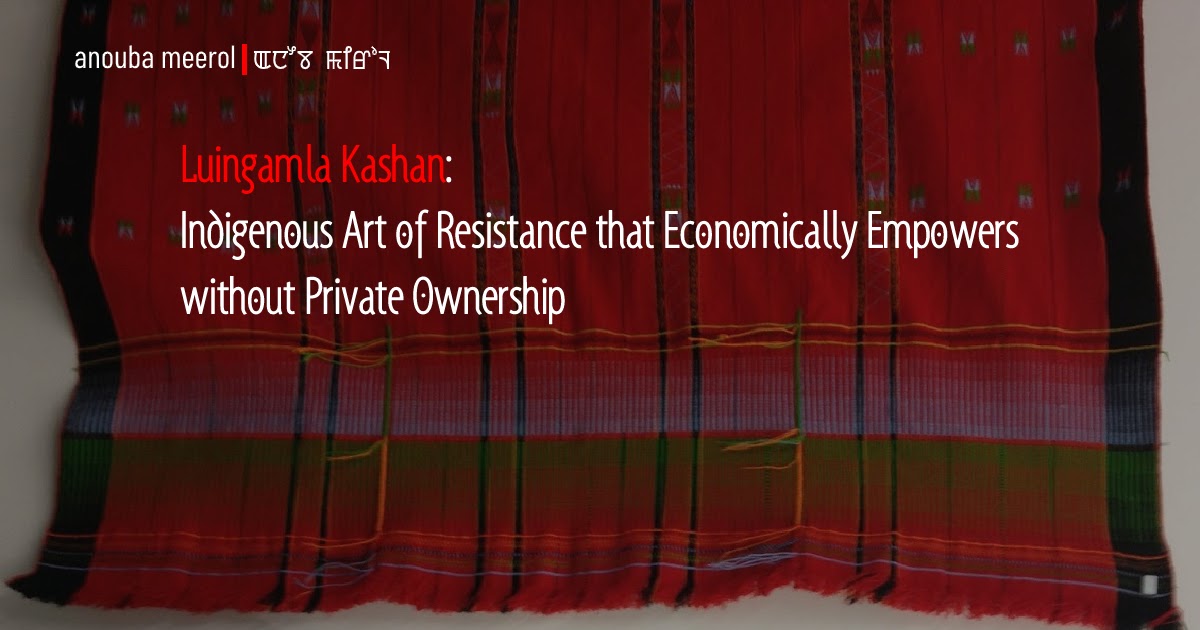

On the afternoon of 24th January, 1986, two Indian army officers entered the house of Luingamla Muinao, a Tangkhul Naga girl in her mid-teens, while she was weaving. They attempted to rape her and she resisted. Her resistance was met with gunshots that killed her on the spot. In her memory, Zamthingla Ruivah, an artist and a weaver, wove a kashan ( a sarong). She named this garment Luingamla Kashan. In this kashan, she uses traditional motifs to symbolise Luingamla’s kindness, courage, unity of the people fighting for justice, and the hardships that came along. Zamthingla said that when the army came, Luingamla was weaving Ruirum Kachon, also known as Leirum Phi among Meitei-s. If one could recollect, it was the same garment that stirred an uproar from among the indigenous communities of Manipur against its appropriation by the mainland Indian. The attempt to forcefully get hold of the indigenous garment was met with resistance to reclaim what is rightfully ours.

Also Read-Leirum Phi branded as Modi gamcha:Threat to Indigenous Culture of Manipur

What is Luingamla Kashan?

Luingamla Kashan is an art of resistance with stories of people’s struggles embedded in its age-old indigenous art motifs through the art of weaving. “The metamorphosis of conflict and pain has produced a timeless art. Luingamla kashan is Ruivah’s book and every woman who wears it is a storyteller” (Celebrating Art, culture & Life, 2019). However, these motifs have lost their traditional meaning. Zamthingla said in an interview that neither does she remember the original meanings nor has she asked the elders. Regarding this amnesia, “Esther Syiem [a professor in the North East Hill University in Shillong] attributed the sense of loss felt by the community, to proselytization by missionaries which wiped away the traditional cultural forms…”(Colah 2008). In addition to this, Zasha Colah (2018) writes: “The suppression of a worldview can be traced to proselytization to Christianity, decades of militaristic violence, factional insurgency and in-fighting, the breaking down of the tribal education systems, shot through by racial difference.” Nevertheless, Zamthingla used the traditional motifs and gave them meanings around the happenings the way she felt as a neighbour, an artist, and a community member who had been receiving atrocities.

Luingamla Kashan has red as its main colour. Zamthingla says that it represents Luingamla’s kind heartedness and the courage to fight till the end of her life. Phorei, a samjet-like motif, which resembles an old traditional bamboo comb, signifies the idea that as a woman, Luingamla must have used her hands to defend herself from the predatory advances of the officers. The garment also features two rows of termites, known as malum, symbolising the unity with which people marched together fighting for justice. On the very next day after her death, “many Tangkhul civil organisations including Tangkhul Shinao Long (TSL) and other students unions held a protest rally in the Ukhrul Town.” “The TSL again organised one big rally in Imphal on 11 March 1986 which was attended by more than 5000 people” supported by other valley-based organisations. Zamthingla says that malum fly out only when it is about to rain, then they fall down and move in two rows; it happens very rarely. Similarly, She finds malum as an apt motif to symbolise the unity of the people after Luingamla’s death as unity happens only once in a while. Then there are the butterfly (kongar) and the frog (khaifa) motifs, representing various civil and military courts that the people appealed to. Between these motifs are the zig-zag lines that symbolise the difficulties and struggles they endured during the course of the case. “They fought this case for four years, the witnesses being called six times to various courts in different villages across Manipur, having to testify in towns far from Ngainga.” (Zasha’s dissertation)

Zamthingla’s Journey to the Kashan

Zamthingla Ruivah remembers Luingamla as this young gentle soul in the neighbourhood who would visit her to see her weave. They were neighbours though not closely related. She recollects from her memory when Luingamla would come running to her house with her brother’s children whenever the military visited her house. Scared and frightened, she often asked Zamthingla if they were there to torture or arrest her father. Those days it was quite common that the army would harass the villagers, Zamthingla narrates. After the incident that killed Luingamla, Zamthingla wanted to do something for the young girl. So, she fasted. She wanted to contribute more, so she wrote three poems and also performed in public service. She even turned it into a song so that more people would know.

Then she, along with others, made a calendar for the year 1990-91 with the story of Luingamla printed on it. Regarding the calendar, she and other villagers again faced a lot of harassment in the hands of the army officers. The officers demanded details on the finances involved in publishing the calendar. After everything was resolved, the army officers offered them lipsticks while letting them go. She and other women folks felt really uncomfortable. “Those lipsticks always stood out to me as a colonial action: the belief that if they showed something shiny she would forget what had happened” (Colah 2018). After years of Luingamla’s death, Zamthingla finally decided to weave a kashan as a tribute.

Role of the Kashan in Empowering Women

At the time of making the kashan, Zamthingla might not have thought of what impact it could bring other than paying tribute to Luingamla’s memory. Later on, as it gained popularity, the villagers decided to make it as a dress code during village festivals. It thus garnered more demand for the garment, allowing many women to engage in weaving throughout the year as a source of income. Zamthingla says that it’s there in all the (around) 232 villages. She believes that there must be around 15-16,000 Luingamla Kashan. Some weavers make around 200 garments/ year. It also continues to live through the time as memory and a means to teach the younger generation of its history. Taking inspiration from Luingamla Kashan, TSL urged the villagers of Rose Machui Ningshen, an 18 year old who committed suicide after Border Security Forces gang-raped her, to make a garment in her memory. The garment they wove in her memory is called Phangrei Kashan or Rose Kashan.

Indigenous Art and Community Ownership

When asked if there was any kind of ownership over the kashan within the Tangkhul Naga community, Zamthingla outrightly denied it and said that she believed it would never be. She had also picked up motifs from the already existing traditional motifs. There is no restriction on who can or how to weave this kashan. The only point to consider is to maintain the basic outlines since those were the defining elements of Luingamla Kashan. She also said that anyone from the community can make it and even remove some of the motifs if they feel there are too many or if they do not have the skill to make it. If there is any ownership, it is the community. Indigenous art has always been passed down from the ancestors through generations. There is nothing indigenous about private ownership of indigenous art.

There have been debates in the indigenous communities in the NE regarding the ownership of the traditional designs, particularly about the garments. Recently, the debate on Leirum phi erupted when it was manufactured and sold as modi gamcha in mainland India. There have been cases where few designers have patented their designs, which are drawn traditional motifs, ensuring that they have individual ownership of these designs. Such concepts of individual ownership of designs, patents or honorarium are alien to Zamthingla Ruivah. It was the community which came together to credit Zamthinga Ruivah as the designer of the Luingamla Kashan. For Ruivah, indigenous art is not about private ownership; it is more about telling stories of the people and building the community. At times when powerful external forces try to capitalize on it, it becomes necessary to reclaim it but as a community ownership.

References:

2019. “Celebrating Art, culture & Life.” 3:3. ARTEM

Colah, Zasha. 2008. Addressing Injustice: Art of the Naga Hills. Master’s dissertation in curating contemporary art. London College of Art.

—.2018. “Disturbed Areas. Individual Imagination. Collective Fictions.” Oncurating. 38.

Mollins, Julie. 2019.”Fellows shape news pathways around Indigenous traditional knowledge at U.N.” Landscape News.

Ningshen, Maireiwon. 2016. “ Human Rights Issues In Manipur And Participation Of Tangkhul Women- Part 3.” E-pao.net.