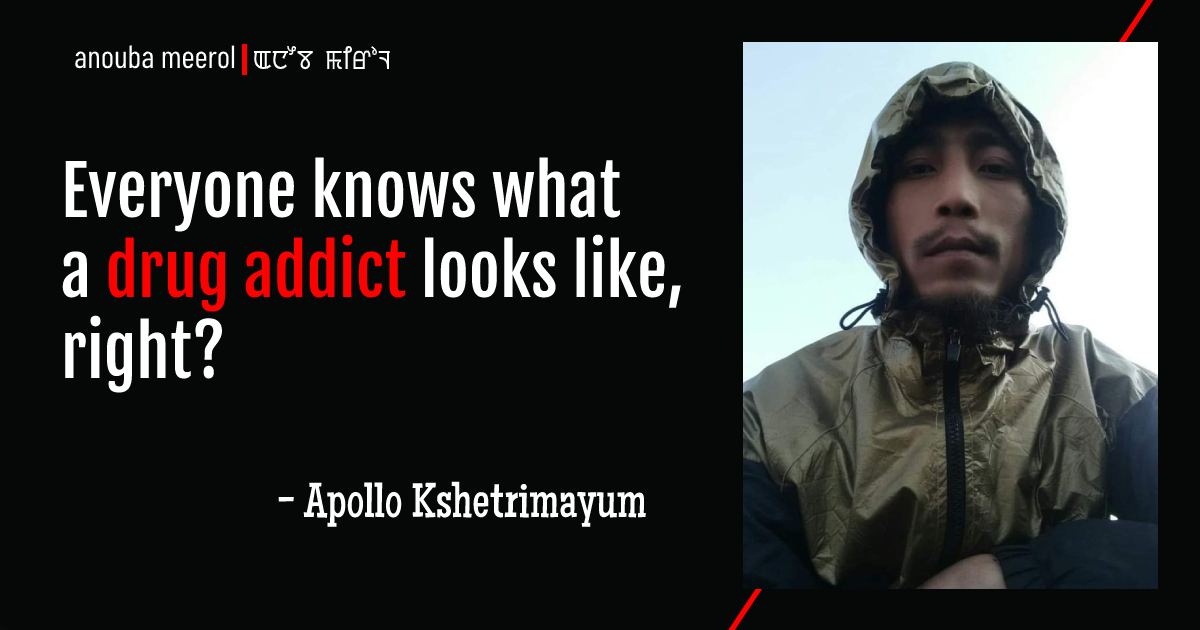

I used to picture a drug addict as someone under a bridge with a needle in his arm. The end of addiction might look that way, but it sure doesn’t begin like that. I never pictured myself as a drug addict until I became one as a teenager.

A Bright Future

As a child, I had a loving family, a love of competition and sports, and good grades. My future was looking bright. What could possibly go wrong?

Like any teenager, I wanted to fit in with kids of my age. Going to parties and drinking alcohol was the norm in high school. Everyone else was doing it. Why shouldn’t I? During my VII standard I discovered that the euphoria from alcohol beat the adrenaline rush from making a game-winning shot . Alcohol became a security blanket for me. It covered up the self-confidence problems that I had secretly felt my whole life. I didn’t think alcohol was a problem. Life continued to go on as I drank it away. This was just the beginning of a long, miserable journey.

When I had my wisdom teeth removed as a sophomore in high school, the doctor prescribed some meds for the pain ( can’t remember the name ). I didn’t know much about drug addiction or what drugs could do to a person’s body. I took more pills than the doctor prescribed. I went through six strips of the stuff in just one week. When I ran out, I started to have frequent headaches and cravings. ( Yes, the Gateway ).

The Face of Addiction

Friends of mine told me where I could buy narcotics so I wouldn’t have to keep going through withdrawal. I started to buy Lobain off the streets. I continued to chase the high because I loved the way it made me feel. As my tolerance for the Narcotic Analgesic increased, I needed more and more to get the effect I wanted. I started to use intravenously that SP. When the pills on the street became shotable , heroin became a viable option.

When I found heroin, I told myself that I will inject it because the needles are just what I love too much. (My mother used to have to hold me down at the doctor’s chamber when I needed a vaccine.) But my addiction told me otherwise. Not more than two weeks into using the drug, I really loved injecting it.

I thought to myself, “This is what falling in love feels like.” Heroin became my best friend, my significant other, and, ultimately off the destructive road. I had a love-hate relationship. After a week or two of using, I felt trapped and scared. I experienced a moment when I knew in my heart there was no turning back. Heroin had total control over my life, physically and mentally. Once that drug was in me, it told me what to do. I didn’t take heroin; heroin took me.

“What I wonder is if those who do take drugs might feel that they can’t be or do anything of value except by magic. Because in the final analysis isn’t that what drugs are: a kind of magic? A magic that will resolve discomfort and will give a sense of being important, perhaps omnipotent?”

I didn’t know how to stop. I tried quitting on my own multiple times, but I never succeeded. This dark time lasted for about years. I went from being a humble guy to a heroin junkie. I pleaded with myself and cried on a daily basis because I wanted to stop using, but my addiction would not allow me to stop. My hatred for myself was so strong and deep. Every day was dark and morbid in my world. My life began to slip away right before my eyes. I have never experienced a more desperate and hopeless feeling than when I sat on the cold, hard bathroom floor getting ready to use once again.

Rehabilitation: A Choice

When I was in standard XI, I had the opportunity to go to a rehabilitation facility for 144 days. About 99% of my mind was telling me not to go. My disease didn’t want me to leave. It wanted me to suffer and ultimately die. But a small part of my mind told me to take advantage of this chance. I took a good look at myself with tears rolling down my cheek and said, “I never want to feel like this again.” This desperation was a precious, lifesaving gift. It was the hardest decision I’d ever made, but I went to rehab.

In rehab I felt safe. It was tough for the first two weeks, but it gradually became easier. Detox was by far the hardest part. The medical staff provided comfort medications to ease the pain, but the process was still difficult. I was drained, both mentally and physically. I felt like I didn’t even know the person who was inside of me.

If it wasn’t for the counselors, I don’t think I would have stayed more than a week. They left their doors open all day in case I needed to talk. They listened to me and comforted me while I blurted out all of my problems. I didn’t trust myself, so I trusted them and the advice they gave me. The counselors in rehab filled me with confidence and hope. I owe them my life.

PS: More will be revealed.

Apollo Kshetrimayum, the author, currently lives with his family in Imphal, Manipur.