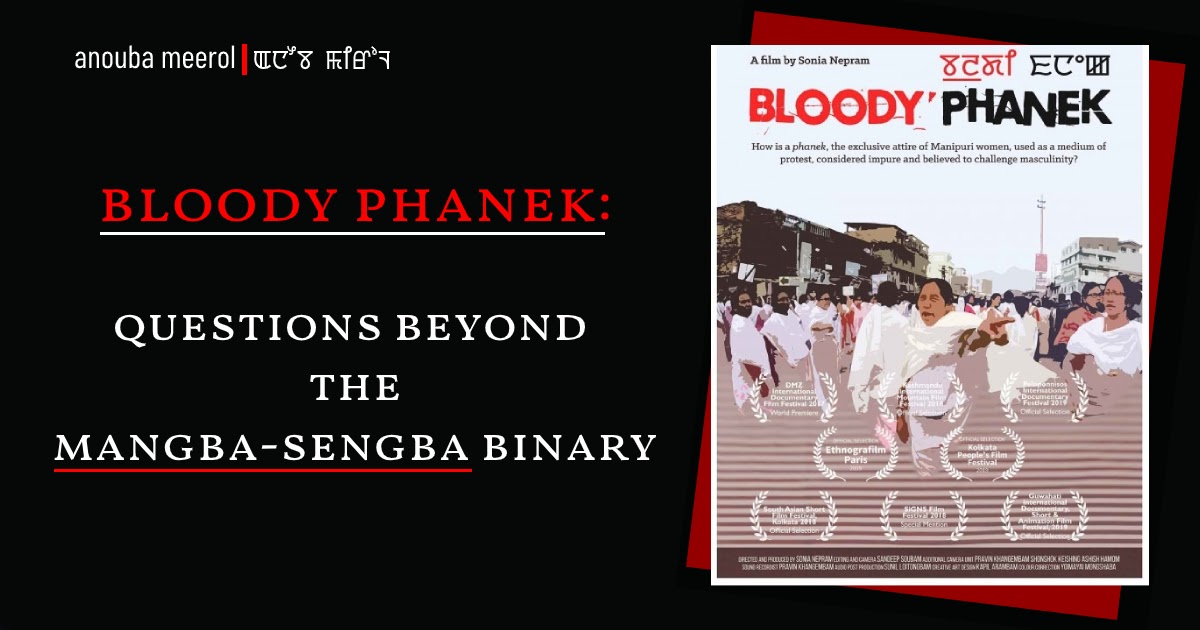

Bloody Phanek is Sonia Nepram’s quest for an answer to the question of mangba-sengba associated with her beloved phanek, which unravels multiple avenues with a plethora of questions about our indigenous history, identity, politics, culture, and society. It further explores varied facets of phanek and its associations with our lives. The film thus opens with one such association: normalized violence and innocence. Two young girls enthusiastically trying to wear phanek nonchalantly react to the sound of an explosion, saying bomb pokhaire (bomb blast). While the premise of the film is phanek mangbra, it delves deeper beyond the mangba-sengba binary and unfolds the complexities of phanek, such as:

- Does it limit one’s freedom or does it empower?

- Does it symbolize femininity or feminine resistance?

- Is phanek mangba a regressive thought or an incomplete thought?

- Why is phanek “imposition” an imposition and other school uniforms not?

- Does hitting a man with phanek perpetuate a kind of disgust associated with it or does it say ‘enough’ to oppressive forces?

Regarding the question of mangba-sengba, the film explores multiple narratives that range from religious rituals to social taboos. However, one thing is certain that most people hold on to this idea just because they have been told so by elders or it has been considered so since the time they can remember. Neither do they have a concrete answer nor do they have ever questioned it. One interesting narrative is the association of phanek with menstruation and childbirth and it being labeled mangba. This hints towards the concept of mangba-sengba that got introduced with the religious encroachment of Hinduism. These practices were used by the feudal lords to collect taxes from people under the lallup system. On the other hand, the film also presents that phanek has, historically, had associations with both men and women in different aspects. It thus raises a question if the idea of phanek mangba was introduced with the coming of Hinduism.

Interestingly, the film explores that men also buy phanek from the marketplaces. The question of mangba does not arise till it is worn by women. So, when does phanek become mangba or is it the female body that makes phanek mangba? On the flip side, the film also reminds us that we find women, phanek, and both together in religious spaces that are considered sacred, in marketplaces, in the fields, various institutional and cultural spaces, and, most importantly, in all the political movements. Phanek-clad women have always been at the forefront. For instance, Meira Paibi movements and Nupi Lan for instance. Considering this aspect, Sonia Nepram challenges her own argument of comfort. While she feels uncomfortable and restricted in her mobility in wearing a phanek, she also gets a sense of defeat seeing these historical movements. At the same time, Mangka Mayanglambam, a folk artist, expresses how she has learned wearing phanek and how she feels more comfortable in phanek now. This brings to another question that isn’t comfort an acquired trait and doesn’t it differ from person to person, generation to generation, culture to culture?

With the question of comfort, the film takes us back to the time when phanek was imposed as a school/college uniform for girls/women. While Sonia Nepram brings forth the question of unfair bias raised at the time of such imposition, the film also presents the perspective of preserving indigenous culture to protect ourselves from extinction because of cultural/religious encroachments. Through the film, Sonia Nepram also questions why the burden of preserving culture is always on women. Men have been wearing pants, pheijom, kurta pyjama even in religious/traditional events, and how indigenous are those? Does it say something about cultural imperialism that uses male attire as its host, men being the dominant group with more power in the society? And does it reflect how the less powerful, here women, are usually the sites of resistance? On a side note, aren’t all school/college uniforms imposed on students? Why is only the “imposition” of phanek seen as imposition?

Another facet of phanek that the film reveals is its association with gender roles and fragile masculinity. While only women are involved in weaving phanek, the film shows that men do not get involved in this profession because it is considered “feminine.” How much of the phanek mangba narrative is applicable here? The narrative seems irrelevant because men are involved in buying phanek in marketplaces. Now, is the reason behind men’s non involvement in weaving more of their fragility or it being a domestic profession or both? On the other hand, the film also shares a glimpse of the prints on phanek and its historical and cultural relevance, which even the current fashion industry holds with respect in showcasing it. But it also makes you question the ethics of the fashion industry that usually capitalizes on such historical and cultural elements.

One very important aspect that the film focuses on is the role of phanek in the movements and protests in the land that we have witnessed over the years. Apart from the phanek-clad women, phanek itself has a strong association with protests against oppressive forces in the land. Two different types of such protests are Heisnam Savitri’s performance in Draupadi and the 12 Ema-s nude protest in front of Kangla. While the former had to face the public wrath, the latter became a symbol of resistance. Both stem from a place of years of unendurable sufferings of the indigenous women in the hands of Indian army, Thangjam Manorama’s case in particular for the 12 Ema-s protest. Women in both events stripped off their phanek as an act of protest against the oppressive forces of Indian army. The only difference, however, is that Savitri’s performance happened in an enclosed art space and preceded the 12 Ema-s protest that happened in a public space. Having said that, people started accepting Savitri’s performance in the later days to come post the 12-Ema-s protest. Nevertheless, she always considered her performance as a protest against the same oppressive regime and not just a mere performance. This brings us to the questions: What is the difference between performance and protest in such cases? Do such performance art-based protests need a precedent like a public protest for it to be accepted as a protest? Do we need acceptance of different platforms/spaces as protest sites? Do place and time decide the value of phanek and its dissociation from the female body?

The most powerful aspect of both forms of protests is the women folks stripping off phanek. It is an act of resistance, asserting that they have had enough and will not take the atrocities anymore. Like Heisnam Savitri said, it is like how indigenous women folks take off their phanek, or just the mention of this idea, to hit indigenous men when the women have had enough of the mistreatment and abuses. The film shows similar instances when school girls take off their phanek to hit police personnel during protests against the state violence and also to protect themselves and their friends.

Does it mean that phanek when separated, in the literal sense, from the wearer symbolizes resistance against the oppressive forces of patriarchy and the state? Is the stripping off also an act of women taking back the agency over their bodies and defying the shame imposed on them about their bodies? Is it taking the powerful oppressive state forces, militarized regimes, and colonial systems head on? Doesn’t the taking off of phanek and hitting police personnel or men mean that women are taking their phanek, which is considered mangba, in their hands to fight the patriarchal state agents or patriarchy in general? Another form in which phanek is used in such protest is the hanging of phanek-s during blockade or in front of mayang lanmi. To the mayang lanmi, it is just a piece of cloth and they do not understand the implication of this practice. However, given the history and root cause behind taking off of phanek and using it against men, isn’t this kind of protest by women folks against the mayang lanmi a message to the people? That it is an act of resistance and a fight against the imperialist state forces because they have been exploiting indigenous women, and men, for years?

By the end of it, the film has already raised multiple questions around phanek related to our history, culture, society, politics, and struggles that the question of mangba-sengba seems almost irrelevant. The film shows that there is a lot more to phanek than just the mangba-sengba binary. The only thing that felt missing from the film is the perspective of nupi manbi and pangal and chingmi women for it’s not just the phanek, but also their identities that deal with this question.