Following is the review of Pheida: Gender at Periphery, a book written by Santa Khurai, Dr. Rubani Yumkhaibam and Bonita Pebam.

“Pheida di thouna yina touphadey [Pheida should not be ill-treated].”

Pheida: Gender at Periphery addresses the concept of gender plurality in our indigenous culture with a thoroughly researched focus on the existence of Pheidas. The book suggests that Pheidas fall beyond the system of gender binary that exists and is celebrated in contemporary Manipur. It re/claims or re/introduces gender plurality in indigenous culture, defined in the book as “the social acceptance and recognition of the existence of a gender identity other than the two genders – man and woman.” This short book also features a brief history of Nupi Maanbi and their struggles. It grounds the contemporary discourse on the Nupi Maanbi community in Manipur in the indigenous texts of the Meiteis, the puyas. Therefore, it could be said that this book is the first of its kind. It is a response to the false understanding that many harbor that Nupi Maanbis do not belong to our indigenous culture.

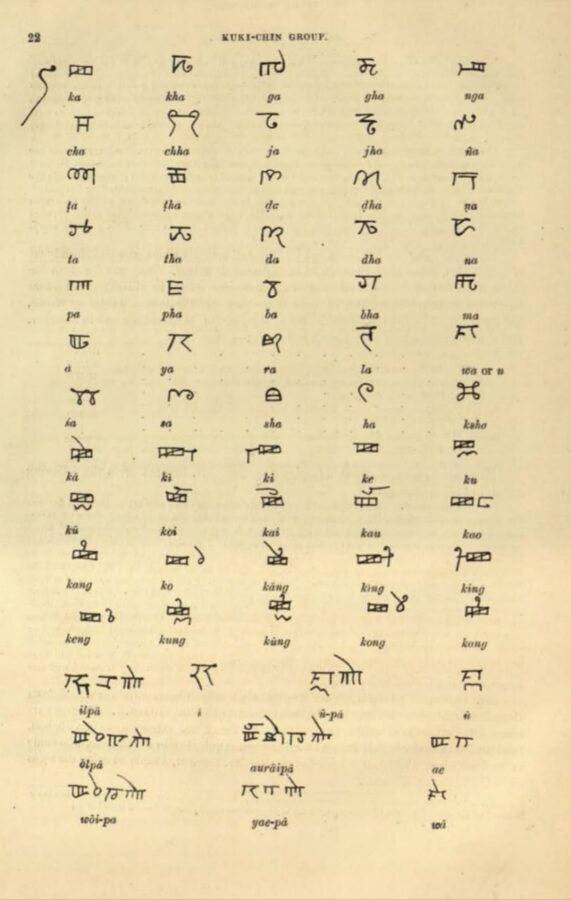

The book takes as sources the puyas such as Mayek Laisak Khangba and Masilney, to argue that gender in indigenous society has never been binary since early period.. First, it highlights how alphabets are assigned genders in the indigenous text, Mayek Laisak Khangba. The alphabet for the sound Ng is said to be Pheida in this puya. Through this the book, Pheida: Gender at Periphery, attempts to establish that in the indigenous world view, other than pa and pi, there is Pheida too. Therefore, this book sheds a new light on our understanding of the history of our indigenous culture. Furthermore, the narrative that the alphabet for the sound Ng is Pheida makes it all the more interesting since Ng is not a sound common in most languages. Though this particular sound is there in some linguistic communities in South East Asia, the mainland Indians find it difficult to pronounce words that start with the sound Ng. Second, the book provides a historical reconstruction of the lives of the Pheida during the Ningthouja Kingdom. Pheidas were entrusted with royal household activities during the feudal days of Manipur. They were closely associated with the king and his household. Pheidas are the only ones who were entrusted to look after women in the king’s household. Third, the book describes the social roles of the Pheidas, such as looking after the market at Pheida Pung, Mapal Kangjeibung or settling disputes in the marketplace. It also lists out various punishments for committing crimes by Pheidas and against them. The book also argues that even though Pheidas were subjected to strict rules of discipline and punishment while working at the royal household, they were at large respected in the Meitei society. They draw this claim from an injunction in the puya Mashilney, which says “Pheida di thouna yina touphadey [Pheida should not be ill-treated].”

Earlier, scholars have equated Pheidas with eunuch. But this book argues that there is no evidence in the literary sources that castration existed in the Meitei society. Therefore, Pheidas cannot be eunuch. To make this claim, they use an injunction in Mashilney puya, which reads “Konung manungda di Nupa amatta changpharoi laina yadey haiba khango, aduna Pheida di nupi ney haibaney ningthow dadi.[ Know that no man can enter the royal palace and it is forbidden by the Gods. So, Pheida is a woman to the King.]” Another case mentioned in the book is that Pheidas were addressed as “Epa by the royal ladies” and as Eyamma by all the guards of different departments in Kangla. Although, there has been no definite explanation on the gender and sexuality of Pheidas, there is a hint about Pheidas to be a community with their gender identity beyond the one assigned at birth.

The book further states that All Manipur Nupi Maanbi Association (AMANA) “officially coined” the word Nupi Maanbi to mean “individuals who are assigned male at birth but whose gender expression is that of the feminine gender” in 2010. The term was conceptualised as early as 2008 by RK Premchand. She heard in the 1970s aged people calling Nupi Maanbi as Pheida. The book also offers a brief definition of Nupi Maanbi community “as an umbrella term that can refer to a wide range of feminine subjectivity and expressions.” It also traces back to the difference between Nupi Saabi and Nupi Maanbi. Coincidentally, maybe, the book mentions the connection between Nupi Maanbi and Mapal Kangjeibung as well. In the later part of the book, it talks about prominent personalities of the Nupi Maanbi movement. It mentions Eney Momon, an artist and an activist in the later half of the 20th century, RK Premchand, an activist who conceptualised the Nupi Maanbi identity, Tom Sharma, a fashion designer of Manipur, Jenny Khurai, a successful make-up artist and Santa Khurai, a well known Nupi Maanbi activist. The book also focuses on the struggle of the Nupi Maanbi community after the formation of All Manipur Nupi Maanbi Association (AMANA) in 2010. It tells us that earlier the activism in the community was only limited to HIV advocacy but now with the formation of All Manipur Nupi Maanbi Association (AMANA), the scope has broadened. It talks about how All Manipur Nupi Maanbi Association was formed for the articulation of their identity, their visibility, for the struggle of their rights and advocacy.

Also read: Notes on Cheitharon Kumpapa, 1500-1550 CE

The book ends with a photo story as an appendix. The photo story narrates Nupi Maanbi community’s movement for political visibility and space, their beauty contests, their participation in indgenous people’s movement in Manipur such as Inner Line Permit movement, the legal and political challenges that Nupi Maanbis have faced in Manipur. For instance, two of the photos convey the erasure of Nupi Maanbi identity from historical sites. An important piece of information on the description of the Pheida Nung, a historical site, has been removed recently. Earlier, in the description of Pheida Nung, it was written that the stone bears the image of “three human figures joining each other,” but this phrase has been removed from the description when the renovation of the site took place in 2020.

All in all, the book is a short and precise narrative on the history of Pheidas and journey of the Nupi Maanbi movement. An important takeaway from this book is what is mentioned in the Introduction part that the group of researchers of this book “encountered a few problems… in the nature of general prejudices against the Nupi Maanbi community” which resulted in “an extreme reluctance on the part of the people to participate”. This adds up another layer of struggle to the lives of Nupi Maanbi researchers on top of the usual challenges of researchers. At the end of this book, one gets an idea of Pheidas and the gender inclusivity of our indigenous society in early times. Now, the question is how and when did the idea of gender plurality and inclusivity get erased from indigenous culture, introducing the concept of gender binary.

This is a well reviewed piece that reflects the deeper ideas of the research using a very simple and understandable languages. The team of Anouba Meerol are highly appreciated.

Thank you for the appreciation.